If You’re Not Ready to Do Hard Things, You’re Not Ready to Be an Entrepreneur

What I learned from 90 minutes with Steven Bartlett during his Asia Tour

I’ve been following Steven Bartlett since 2018. Back then, he was building Social Chain, a social media agency that would eventually be valued at £200 million. I watched him evolve from agency owner to Europe’s youngest Dragon on Dragons’ Den, to host of The Diary of a CEO - one of the world’s biggest podcasts - to investor backing some of the most exciting companies globally.

Here in Southeast Asia, we rarely get podcasters of his caliber coming through. Most speaking tours skip our region entirely. So when Steven announced he was doing an Asia tour, it was beyond exciting.

I wasn’t expecting platitudes or motivational fluff. Steven doesn’t do that.

For 90 minutes, Steven shared stories from his interviews with CEOs, founders, and former political leaders. He was dishing it out as it is, the hard stuff, the stuff that most people don’t have the grit to endure.

Let me share what actually stuck.

Your Dog, or Your Dream?

In 1975, Sylvester Stallone was so broke he sold his dog outside a 7-Eleven for $40.

Three days later, inspired by a Muhammad Ali fight, he wrote the Rocky script. Studios loved it. They offered him $25,000. Then $50,000. Then $150,000. Finally $200,000.

He said no to all of it.

Why? Because they wouldn’t let him star in it.

This is a man who just sold his best friend because he couldn’t afford dog food. Turning down $200,000.

Eventually, a studio offered $25,000 for the script AND let him be the lead. He took it. First thing he did? Bought his dog back.

The lesson isn’t about Stallone’s conviction. It’s simpler: What are you actually willing to lose?

Most of us say we’d do anything for our business. But we won’t risk looking stupid on LinkedIn. We won’t have the hard conversation with our co-founder. We won’t fire the client who’s killing our team’s morale.

Stallone sold his dog. What’s your equivalent?

Do Things That Suck (Your Brain Will Thank You)

In 1884, Theodore Roosevelt’s wife and mother died on the same day. Valentine’s Day. In the same house.

He wrote in his diary: “The light has gone out of my life.”

Then he went to the Badlands of North Dakota—one of the most brutal environments on earth. Temperatures from -41°C to 47°C. He’d wake at 4am to hunt and work the land.

Years later, he said: “That’s where I became a man.”

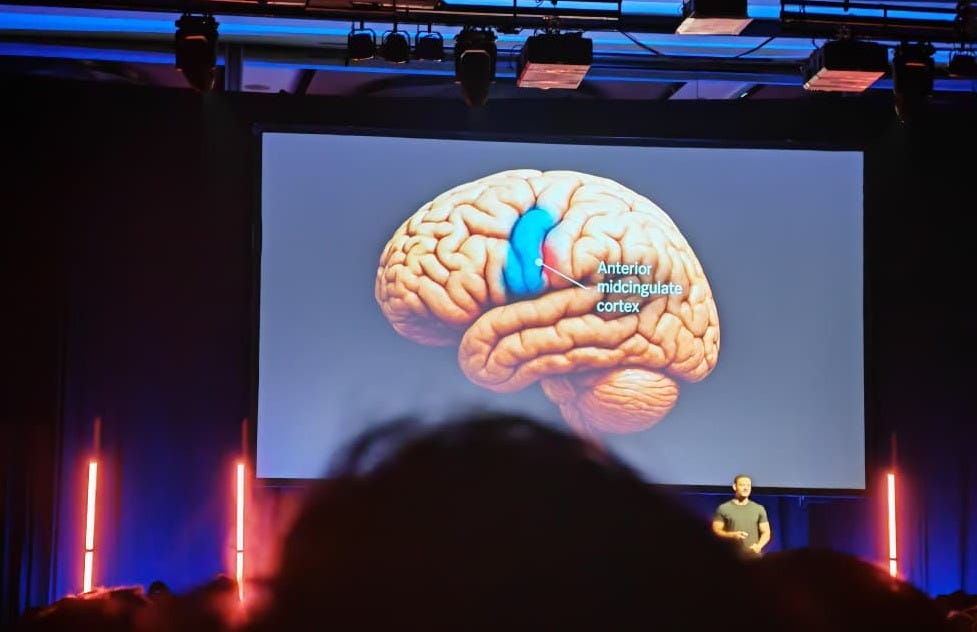

Stanford researchers discovered why this works. When you do hard things—things you actively don’t want to do—a specific part of your brain grows. It’s called the anterior mid-cingulate cortex.

This region controls willpower and discipline.

People who live past 100? Their anterior mid-cingulate cortex is 25% larger than average.

But here’s the catch: it only grows when you do things you hate.

Not things that are just difficult. Things you actively resist.

The cold email you’re avoiding. The financial model you keep putting off. The product feature you need to kill.

Every time you do the thing you’re avoiding, you’re literally building brain tissue that makes the next hard thing easier.

Roosevelt didn’t heal by resting. He healed by choosing the hardest possible thing.

What’s your Badlands?

54% of Success is Just Not Screwing Up

Roger Federer won only 54% of the points he played in his career.

Read that again.

One of the greatest athletes of all time lost almost half the time not because his opponent was better, but because he made unforced errors.

Steven’s friend Ashley, who he’s watched play tennis for 17 years, has the same pattern. Under pressure, Ashley makes errors he’d never make in practice. Simple mistakes. The kind that make you want to throw your racket.

The problem? When you’re overwhelmed, your emotional brain hijacks your logical brain. You stop thinking clearly.

Sir David Brailsford, who transformed British cycling, told Steven something similar: “The best performances happen when athletes stop thinking. They’re so in the zone, they don’t even remember the race afterward.”

Here’s what this means for you:

Your biggest mistakes don’t happen because you lack skill. They happen because you’re emotional.

The panicked hire. The reactive email. The decision made at 11pm when you’re spiraling.

Build a circuit breaker. When you feel your brain going sideways, have a pattern interrupt. A question you ask yourself. A breathing technique. A 10-minute walk.

The game isn’t about never making mistakes. It’s about making fewer unforced errors than your competition.

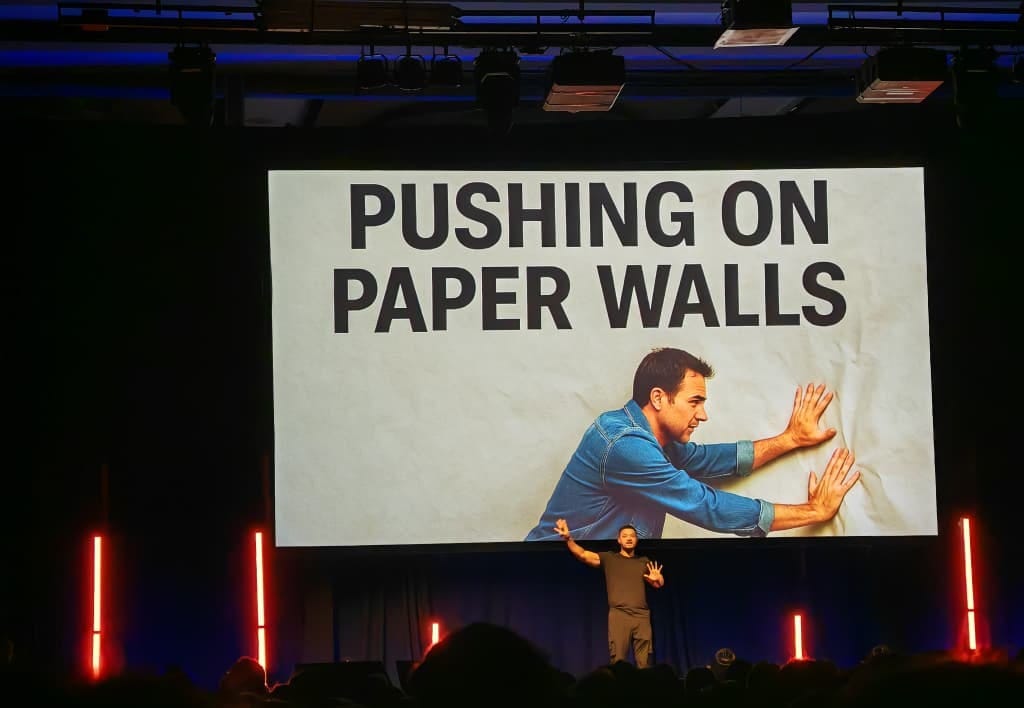

Most Walls Are Made of Paper

In 1970, Bernard Sadow invented wheeled luggage.

Every manufacturer rejected it. “Men won’t buy it. Real men carry their luggage.”

Department stores refused to stock it.

One buyer finally agreed—but only in the youth section, because “young people might be open to weird ideas.”

Now? We can’t imagine luggage without wheels.

Roger Bannister ran a 4-minute mile in 1954. Scientists said it was physically impossible. Your heart would explode.

Within weeks of Bannister breaking the record, 16 other people did it too. Now college kids do it casually.

The barrier was never real. It was a collective belief—a paper wall.

Every industry has these.

“Social media agencies charge monthly retainers.”

“Fashion shows happen twice a year in Paris.”

“Luggage doesn’t have wheels.”

“That project takes two weeks because that’s how long it’s always taken.”

Steven shared a story about his own team. He asked his designer to create something. The designer said: “Two weeks.”

“Why two weeks?”

The designer explained the process.

“But why can’t we do it now?”

After several rounds of “why,” they discovered 70% of the timeline was just habit. “The way we’ve always done it.” They finished it that day.

Steven’s first business succeeded partly because he didn’t know the “rules” of social media agencies. So he charged differently and won clients from agencies that had been around for decades.

Your competitive advantage might just be your ignorance of how things are “supposed” to work.

Pick any workflow in your business. Ask “why” five times. Watch what crumbles. Most of your constraints aren’t real - they’re just paper walls no one’s pushed on yet.

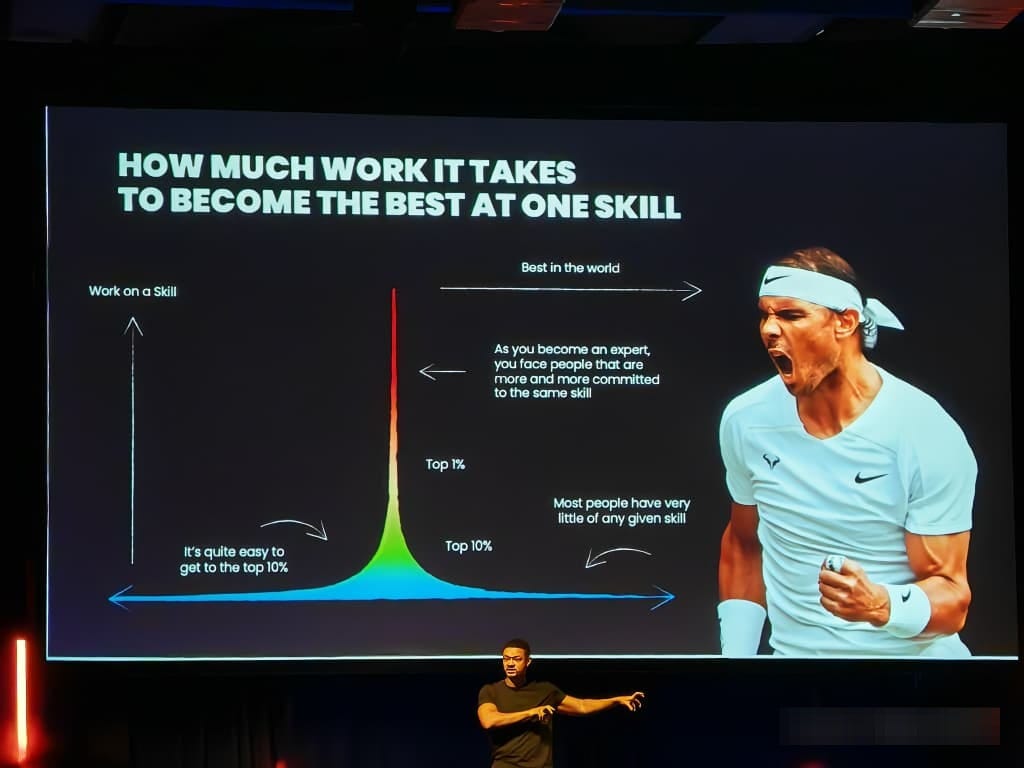

You Don’t Need to Be the Best at One Thing

Steven asked: What’s the most important skill to learn?

Then he watched Vasyl Lomachenko box. Lomachenko’s footwork is supernatural. Record: 396 wins out of 397 amateur fights.

The secret? When he was 14—already a great boxer—his father pulled him out of boxing for four years to study Ukrainian dance.

Lomachenko isn’t the best boxer. He’s the only dancer-boxer.

The math is simple:

Top 1% in one skill? Nearly impossible.

Top 10% in two complementary skills? You’re now top 1% of that combination.

Top 10% in three skills? Top 0.1%.

Cristiano Ronaldo isn’t #1 in speed, dribbling, or shooting. But he’s top 10% in all of them. That combination made him the best.

Steve Jobs wasn’t the best technologist. But he combined tech with calligraphy and design—random classes from college. That’s why the iPhone has beautiful typography.

For you:

Don’t just get better at what you do. Add a rare complementary skill.

Marketing + AI

Finance + storytelling

Development + design

Personal training + content creation

The future leader of your industry won’t be the best at the core skill. They’ll have the rarest combination.

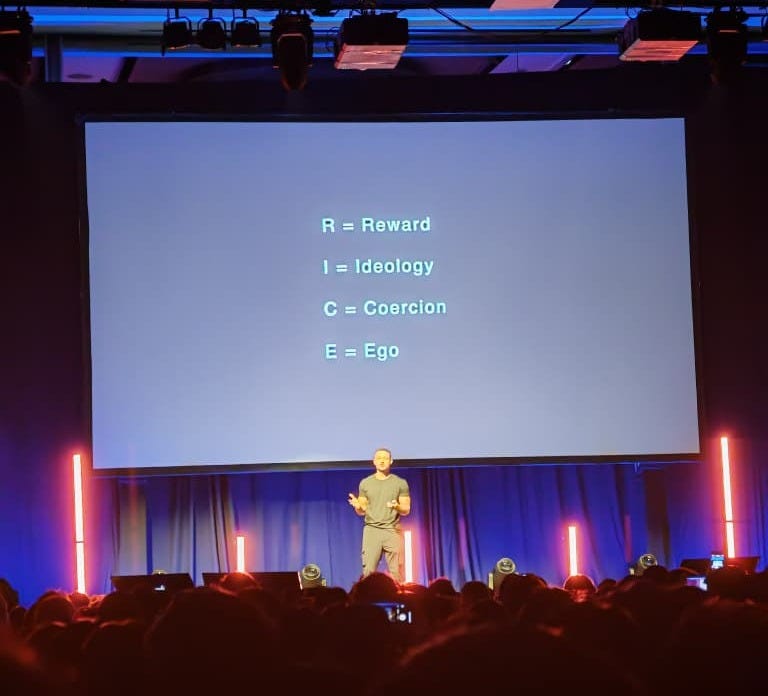

Money Isn’t the Game

A company offered a founder $100 million for his business.

He said no.

They raised it. He kept saying no.

Finally, they offered $80 million—but put his name on the building forever and made him an honorary advisor.

He took it. $20 million less than the previous offer.

Why?

His ego needed recognition. His ideology needed to honor his father, who doubted him when he started.

Most entrepreneurs compete on reward. That’s the wrong game.

If you want someone to join your team, invest in your company, or partner with you, understand two things:

Their ideology - What they believe is right. Their values. Their mission.

Their ego - How they see themselves. Their identity.

A CIA recruiter told Steven this is how you get anyone to do anything. Not through money. Through understanding what drives them.

Make them the hero of their own story. Not a supporting character in yours.

What This Means for Me (And Maybe You)

I’ll be honest—I’m in the messy middle right now.

I’ve built something before. It worked. But now I’m starting again, and this time I’m pushing into territories where I’m not the expert. Where I don’t have all the answers. Where I need people to trust me in areas I’m still figuring out myself.

It’s uncomfortable as hell.

The skill stacking section hit me differently because that’s exactly where I am. I’m trying to take what I know and layer it with something new. Not because it’s trendy, but because the combination feels right - even if I can’t fully articulate why yet.

I’m still figuring out my “why.” I know I like building things. I’m drawn to understanding people, to the psychology behind why we do what we do. I love the process of taking something raw and shaping it into a brand that resonates. But the clean, one-sentence mission statement? I’m not there yet.

And maybe that’s okay.

What Steven’s session reminded me—especially the Roger Federer story—is that I don’t need to win every time. I’ve spent so much of my career trying to be right, to nail it on the first try, to prove I belong.

The game isn’t about perfection. It’s about showing up, making fewer mistakes than yesterday, and having the guts to try things that might not work.

My career has been anything but traditional. I’ve pivoted when the “smart” move was to stay the course. I’ve pushed on paper walls without even realizing they were paper.

But right now, the hardest thing isn’t external. It’s internal.

It’s trusting myself in unfamiliar territory. It’s doing hard things when there’s no guarantee they’ll pay off. It’s building something new when the old way was comfortable.

If you’re reading this and you’re in a similar spot - you don’t need to have it all figured out. You don’t need to be the best yet. You just need to be willing to do the hard thing when it shows up.

And it will keep showing up.

The only question is: will you choose it before it chooses you?

If you’re building something, I’d love to hear what hard thing you’re facing right now. Sometimes just naming it makes it less scary.